Would you pay to use Twitter? A service called

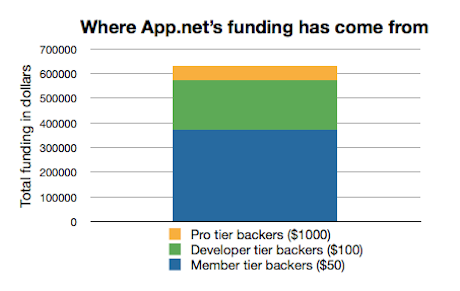

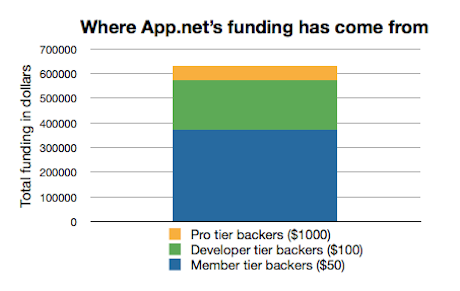

App.net has just indicated that at least some people would, by hitting a target of raising $500,000 in funding from individuals paying $50, $100 or $1000 to set up a Twitter clone where "users and developers come first, not advertisers".

The brainchild of Dalton Caldwell, a San Francisco-based developer who was one of the people behind the "web 2.0" resurgence in 2006, the scheme

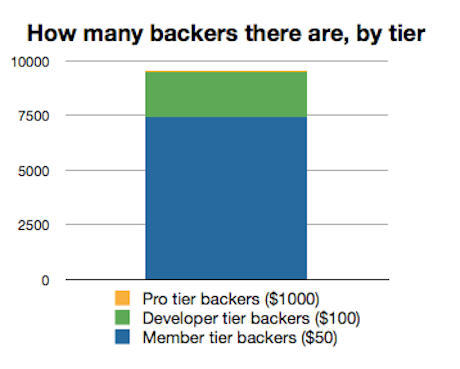

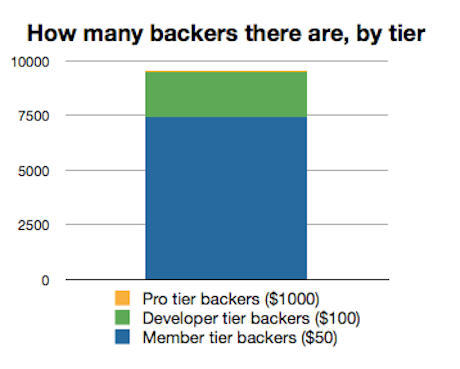

hit its target funding on Sunday evening more than a day ahead of its deadline. At the time of writing 7,448 people are offering to pay the base $50 level for access to post to the service, 2,010 paying $100 to be developers with access to back-end functionality, and 59 paying $1,000 for "pro tier" access including

phone support and a personal meeting with Caldwell. (See the

graph of funding sources.)

Where App.net's funding has come from, by tier (member, developer and "pro")

Where App.net's funding has come from, by tier (member, developer and "pro") App.net members, by tier

App.net members, by tierCaldwell began building the service because he, along with a number of other developers, had become uneasy about Twitter's approach to developers building third-party applications, where it has blocked a number of sites and services from accessing its API, the "hook" that external

software needs to provide Twitter functionality. As Twitter tries to generate revenues from its fast-growing user base, it has been putting more restrictions on what developers can do - leading to restlessness among those who have built apps for it.

"We believe that advertising-supported social services are so consistently and inextricably at odds with the interests of users and developers that something must be done," Caldwell

wrote on the App.net signup page.

Speaking to Technology Review, he said that "Twitter created as fundamental a technical innovation as e-mail and HTML itself, and they totally blew it." Twitter has been tightening access to its API and the extent to which developers can use it progressively since 2010.

The most audacious aspect of the project is that unlike almost every other service coming out of San Francisco - and in stark contrast to Twitter, which is and has been free to post and develop for - App.net charges its users.

In a

blog post in July, Caldwell says that the key problem with Facebook and Twitter, which offer an ad-supported platform, is that "this 'platform" word starts to get very troubling when talking about

business models. Building on top of a platform is a foundational risk, and if your platform decided one day that it doesn't like what you are doing, or likes what you are doing so much they want to compete with you, it's Very Bad. Your platform partner can easily damage your quality of service, or simply shut you down. If that happens, your business is dead."

Caldwell argues that if users and developers are paying to use the service, then the operator has no incentive to shortchange either - and no incentive either to intrude into eithers' experience by inserting adverts into feeds (as both Facebook and Twitter do).

There are relatively few examples of paid-for alternatives to free services which offer essentially the same functionality as the free version. One is

Pinboard, a paid-for bookmarking service that offers the same functionality as the free

Delicious. While Delicious is free to use, on Pinboard each user pays a one-off fee on joining for lifetime use; the fee rises with the number of users. (Guardian Technology has been a paid-up user of Pinboard since mid-2011.)

In general, though, paid services struggle to grow as quickly or as large as free ad-supported services because users are reluctant to provide upfront payment to a service that may fail, and where its value to them may be different from that being charged, because peoples' earning power varies widely.

By contrast ad-supported services in effect charge people for their attention to adverts - and everyone has 24 hours in a day, so in effect everyone pays the same attention cost (though perhaps not potential earnings cost) for an advert.

Some services then offer "premium" services by exploiting peoples' ability to pay not to have their attention diverted by ads, or for extra functionality - creating "freemium" services with different tiers of users.

Caldwell though aims to buck the trend for services to try to grow entirely on ad-supported models. The idea of app.net grew from a blogpost on 13 July, in which he

announced an "audacious proposal". In it, he pointed to the problems he perceived with SourceForge, an ad-supported code repository: "the site was designed to squeeze every lasat advertising penny out of you," Caldwell wrote. By contrast, he pointed to Github, a freemium service which offers some facilities for free and charges for others.

"Contemplate for a moment how scary a theoretical purely ad-supported Dropbox would be," he noted, referring to the cloud-based freemium storage service which offers a shareable file locker service. "I can easily imagine the overly-cheerful corporate blogpost explaining why placing ads in my personal documents, or selling the file-listing of my music collection to the music industry, or shutting down IFTTT [If This Then That, a service that allows automation of web services] API access is 'important to the health and welfare of the community.' I happily pay to avoid that nightmare scenario, wouldn't you?"

At its core, Caldwell's proposal - and its success so far, attracting just under 10,000 paying customers - points to a rumble of dissatisfaction within some parts of American culture with the pervasive nature of advertising there. "Why isn't there an opportunity to pay money to get an ad-free feed from a company where the product is something you pay for, not, well, you?" Caldwell asks.

He points to Imeem - a social media sharing company he founded and ran - which, despite raising more than $50m in venture capital and selling more than $2m of advertising per month at its peak, was sold to MySpace in 2009.

Instead, he revealed, he has been focussing on a service called App.net, "a paid service for mobile application developers", with a consumer-focussed iOS app and service.

Caldwell thinks that the 10,000 figure for paying backers is sufficiently large to mark a critical mass - as long as the backers are the right people. Paul Graham, a venture capitalist with long experience in the software industry, suggests that "a search engine whose users consisted of the top 10,000 hackers and no one else would be in a very powerful position despite its small size".

Certainly App.net has garnered a number of high-profile names, including Stephen Fry and many of the people who were early adopters of Twitter.

What is less easy to know is how App.net will fare in what will become a war for time and attention with bigger, established sites and services. Facebook has 955 million users; Twitter, more than 100 million. Will 10,000 be enough to start changing that?